Terence “Terry” Patrick O’Neill was born on 30 July 1938 in Heston, West London. For a time, the young O’Neill was expected to be a priest, but soon found his true calling to be music. “I was told I had too many questions to be a priest” he would later remark. “I loved jazz and my heart was set on being a jazz drummer.” As an aspiring drummer, O’Neill sought employment at BOAC (British Overseas Airways Corporation, later British Airways) thinking a job at an airline would enable him to travel to New York City and play in the jazz clubs in between his work. Finding no steward jobs available, he was advised to take a position within the photography department.

Working with photographer Peter Campion, who was a decade older than the young O’Neill, Campion took a shine to the budding jazz drummer and thought “he had the eye” and “what it takes to be a great photographer.” O’Neill later remembered “[Campion] would bring in all these books for me to look at. He literally showed me what photography could be.”

Whilst working at BOAC, O’Neill chanced upon a photograph that would forever change his life. “Part of my work was to take photographs of people arriving and departing at the terminals. I happened upon a very well-dressed bowler-hatted man, taking a quick nap in the departures area, and he was surrounded by African chieftains, fully clad in their regalia. Soon after, I was approached by an editor who told me that they wanted to show the photo to his paper. The man napping turned out to be then Home Secretary Rab Butler. The paper ran my photo and I was off and running. I was offered a job at the Daily Sketch where I worked for several years before going out on my own.”

Some of the earliest photographs by Terry O’Neill happened to be some of the first photographs of musicians who would go on to define an era; the Swinging Sixties was upon England and O’Neill and his camera captured it all. “I was asked to go down to Abbey Road Studios and take a few portraits of this new band. I didn’t know how to work with a group – but because I was a musician myself and the youngest on-staff by a decade – I was always the one they’d ask. I took the four young lads outside for better light. That portrait ran in the papers the next day and the paper sold out. That band became the biggest band in the world; The Beatles.”

Following his work with The Beatles, he was called by Andrew Loog Oldham, the young manager just starting out with his new band, The Rolling Stones. “Terry O’Neill captured us on the street, and that made all the difference. Terry captured the time” Oldham recalls. Keith Richards would also remark that O’Neill was “behind the lens, everywhere, always.” O’Neill’s photographs of The Rolling Stones would be instrumental in the band’s early success.

O’Neill remembered “I started at the top and never looked back.” Following his work with The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, more stars started to align, and O’Neill began to visually define the 1960s by working with a who’s who in music, film, and celebrity; Michael Caine, Sean Connery, Audrey Hepburn, Elizabeth Taylor, Terence Stamp, Jean Shrimpton, Tom Jones, and ending the decade with Frank Sinatra. O’Neill was also one of the first photographers to work with a new franchise starring Sean Connery as James Bond. O’Neill went on to work on several Bond films throughout the decades, including several with Roger Moore.

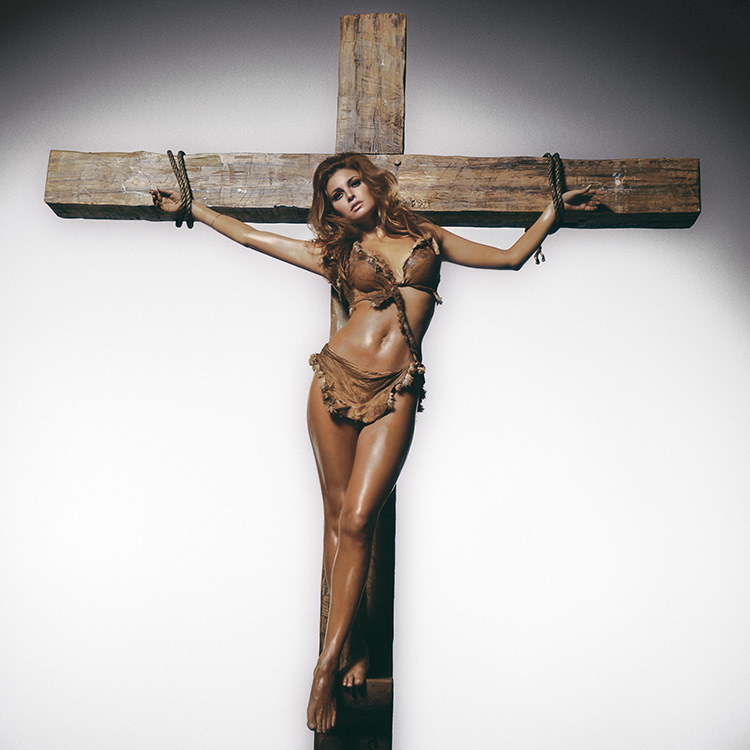

Raquel Welch, who worked with O’Neill several times throughout her career, notes that “I never liked being photographed . . . until I started working with Terry. [The first time I worked with him] I thought, glancing in his direction, he’s attractive! ‘Hey Rocky’, he smiled. How did he know my nickname? I smiled back and thought that’s a cool way to break the ice.”

Besides screen stars and musicians, O’Neill also captured images of leading athletes and politicians. A photograph of the former Prime Minister Winston Churchill leaving hospital in 1962 taken by O’Neill also produced another image – a crowd shot of the ambulance driving away taken by an unknown photographer. In the crowd, a young Terry O’Neill can be seen running in the other direction, cameras slung around his neck. “I was rushing to the dark room with my film” he laughed.

“Terry was a ‘historian’ whose camera captured the resurgence and energy of this revolution” notes Michael Caine. “I can think of no other photographer who has contributed so much to our heritage.”

Introduced to Frank Sinatra by Ava Gardner, O’Neill and Sinatra struck up a working and personal relationship that would last through the icon’s life. Some of the most iconic images of Sinatra from 1968 onwards were taken by O’Neill, including the celebrated “Sinatra on the Boardwalk”, which hangs in prestigious museums and private collections worldwide.

As the 1960s ended, O’Neill continued to be one of the most sought-after photographers in the world, working with Brigitte Bardot, Roger Moore, Paul Newman, Clint Eastwood, Robert Redford and two new singers about to take the world by storm.

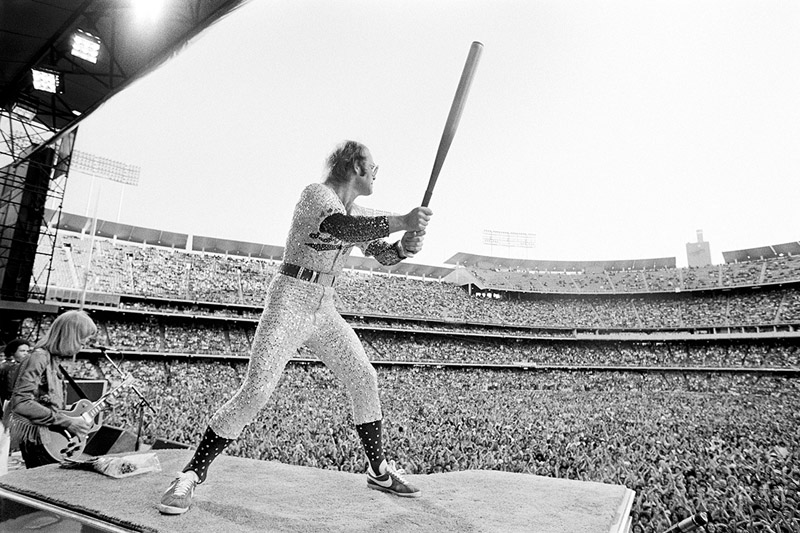

O’Neill took it upon himself to seek out Elton John, a rising young star, after hearing him on the radio in 1971. “I’d often be asked by the papers – who’s next – who is going to be the next big rock ‘n roll star. And that was Elton John.” O’Neill spent the next few decades working with Elton John, including the famed two day concert series at Dodger Stadium in October 1975. Many of O’Neill’s images were used as reference material in the recent film ‘Rocketman’ and it is O’Neill’s portrait of the artist that adorns John’s recent memoir, Me. Elton John remembers “looking at Terry’s photographs is like gazing through a window at the most extraordinary and exciting moments of my life.”

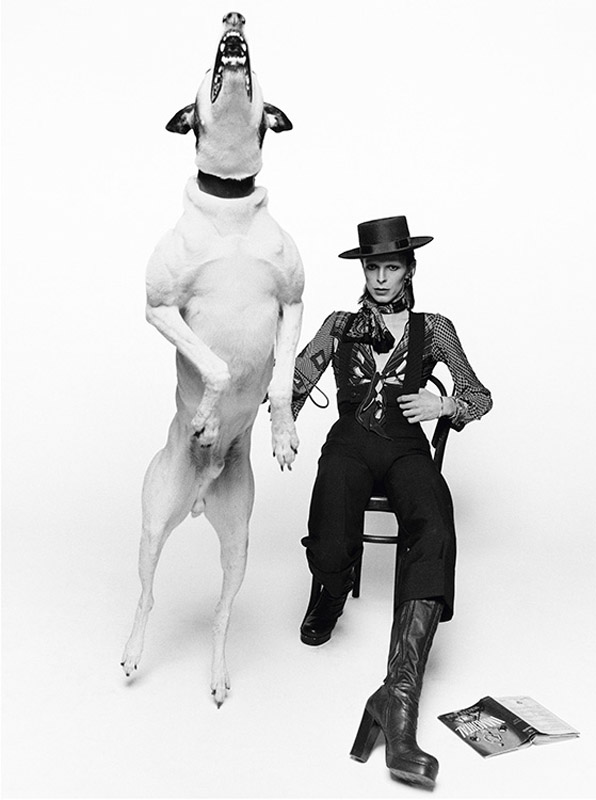

In late 1973, O’Neill was invited to the Marquee Club in Soho to a closed-set last performance of Ziggy Stardust by David Bowie for American television. This invite would result in several legendary photo sessions, including the now iconic “Jumping Dog” image that was highlighted in the recent ‘Bowie Is’ exhibitions that premiered at the V&A Museum in London before a worldwide tour.

Besides music, O’Neill was still connected to Hollywood, and an assignment covering the winner of the 1977 Academy Award would again produce an iconic image.

Faye Dunaway was the strong favourite to win the award for her work in the 1976 film ‘Network.’ O’Neill, who did not know the actor, convinced the star to meet him at the pool of the Beverly Hills Hotel at dawn if she won. “I told her to bring the Oscar” he remembered. “I always wanted to capture what it felt like the next day, not the image you’d see in the papers of the star holding up the award with all the lights and camera – but I wanted to capture the moment it all sinks in, that your asking price has just skyrocketed and you can have any role in the world. I wanted to capture the morning after.” A blurry-eyed winner met O’Neill at the pool where the star posed at a table with the morning papers, a tray of coffee and her gold statue. Widely recognised as one of the most important images of Hollywood, the ‘Faye at the pool’ image further cemented O’Neill as an iconic photographer.

As the 21st century began, O’Neill focused the last decades of his life on exhibiting, publishing and discussing his work. “I love meeting people at events, whether that be exhibition openings or book signings – I never imagined the work I did more than fifty years ago would mean so much to people today” O’Neill would go on to say.

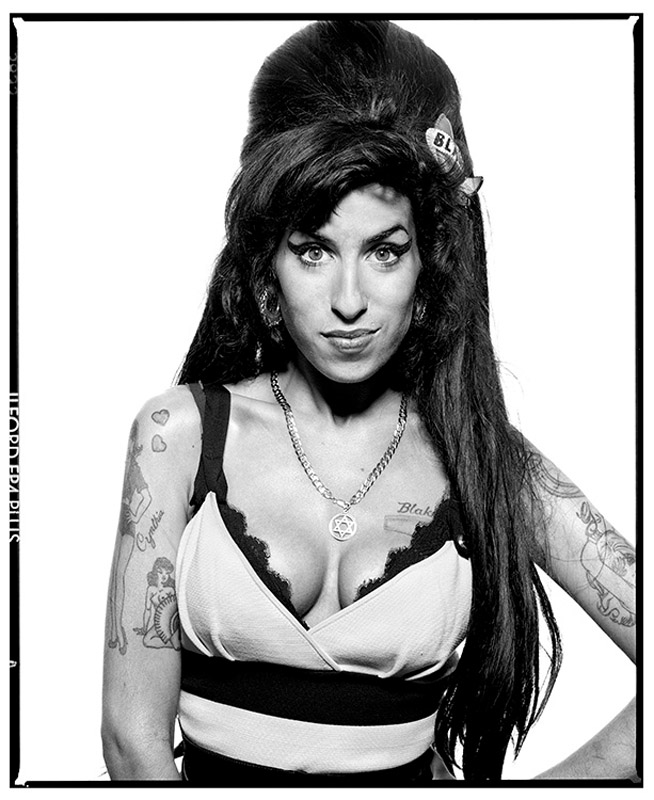

Robin Morgan, the former editor of The Sunday Times Magazine and CEO of Iconic Images sums up Terry O’Neill’s career perfectly; “No other photographer worked the frontline of fame for so long and with such panache. Terry chronicled the cultural landscape for six decades from HM Queen Elizabeth II, Winston Churchill to Nelson Mandela, The Beatles to Amy Winehouse, Muhammad Ali to the biggest stars of film and stage. They all dropped their guard to his mischief, charm and wit. It explains why so many of his subjects, from Raquel Welch to Sir Michael Caine, remained lifelong friends.

“Often an old flame was in town and wanted dinner so he would call me and plead with me to chaperone him - he didn’t want to be alone with her. I’d find myself playing gooseberry to him and some of the most famous women - and egos - on the planet.

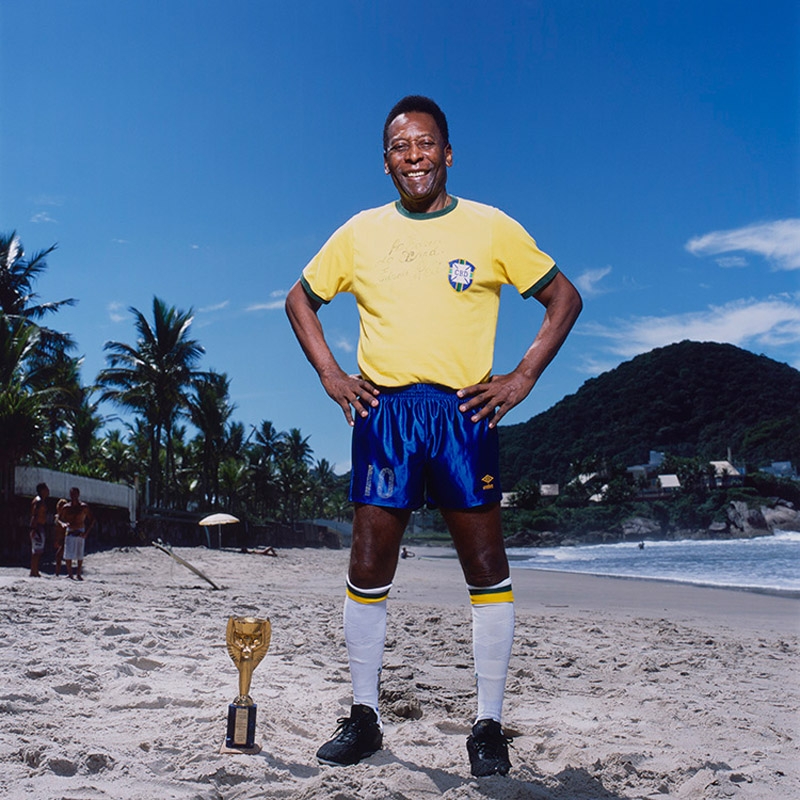

“I remember Terry and I having lunch with Pele at his beach house in Santos, Brazil a couple of years ago, swapping stories about their mutual friend, England’s World Cup Winning captain Bobby Moore. They were just a couple of football fans dissecting the modern game. (Suddenly, Pele went inside and re-appeared with the Jules Rimet trophy that England had won in 1966. THE World Cup, later presented to Brazil having won it a third time in 1970 - and then given to Pele by the nation. It had to be prised from Terry’s grasp).

“By the end of his life his work was hanging in more than 40 galleries and museums around the world” Morgan notes.

Terry O’Neill was awarded the Royal Photographic Society Centenary Medal in 2011 in recognition of his significant contribution to the art of photography and an Honorary Fellowship of The Society. Earlier this year, O’Neill was awarded a Commander of the British Empire (CBE) for services to Photography in this year’s Queen’s Birthday Honours list. O’Neill noted at the time that it was "a huge honour. And I’m incredibly humbled by it. It’s a real recognition for the art of photography, as well. This isn’t just for me of course, it’s for everyone who has helped me along the way. Thank you, from the bottom of my heart."

Terry O’Neill passed away, aged 81, quietly at home after a long illness.